Human communication is understood in various ways by those who identify with the field. This diversity is the result of communication being a relatively young field of study, composed of a very broad constituency of disciplines. It includes work taken from scholars of Rhetoric, Journalism, Sociology, Psychology, Anthropology, and Semiotics, among others. Cognate areas include biocommunication, which investigates communicative processes within and among non-humans such as bacteria, animals, fungi and plants, and information theory, which provides a mathematical model for measuring communication within and among systems.

Generally, human communication is concerned with the making of meaning and the exchange of understanding. One model of communication considers it from the perspective of transmitting information from one person to another. In fact, many scholars of communication take this as a working definition, and use Lasswell’s maxim, “who says what to whom in which channel with what effect,” as a means of circumscribing the field of communication theory. Among those who subscribe to the transmission model are those who identify themselves with the communication sciences, and finds its roots in the studies of propaganda and mass media of the early 20th century.

Other commentators claim that a ritual process of communication exists, one not artificially divorcible from a particular historical and social context. This tradition is largely associated with early scholars of symbolic interactionism as well as phenomenologists.

Constructionist Models

There is an additional working definition of communication to consider that authors like Richard A. Lanham (2003) and as far back as Erving Goffman (1959) have highlighted. This is a progression from Lasswell’s attempt to define human communication through to this century and revolutionized into the constructionist model. Constructionists believe that the process of communication is in itself the only messages that exist. The packaging can not be separated from the social and historical context from which it arose, therefore the substance to look at in communication theory is style for Richard Lanham and the performance of self for Erving Goffman.

Lanham chose to view communication as the rival to the over encompassing use of CBS model (which pursued to further the transmission model). CBS model argues that clarity, brevity, and sincerity are the only purpose to prose discourse, therefore communication. Lanham wrote, “If words matter too, if the whole range of human motive is seen as animating prose discourse, then rhetoric analysis leads us to the essential questions about prose style” (Lanham 10). This is saying that rhetoric and style are fundamentally important; they are not errors to what we actually intend to transmit. The process which we construct and deconstruct meaning deserves analysis.

Erving Goffman sees the performance of self as the most important frame to understand communication. Goffman wrote, “What does seem to be required of the individual is that he learn enough pieces of expression to be able to ‘fill in’ and manage, more or less, any part that he is likely to be given” (Goffman 73) Goffman is highlighting the significance of expression. The truth in both cases is the articulation of the message and the package as one. The construction of the message from social and historical context is the seed as is the pre-existing message is for the transmission model. Therefore any look into communication theory should include the possibilities drafted by such great scholars as Richard A. Lanham and Erving Goffman that style and performance is the whole process.

Communication stands so deeply rooted in human behaviors and the structures of society that scholars have difficulty thinking of it while excluding social or behavioral events. Because communication theory remains a relatively young field of inquiry and integrates itself with other disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, and sociology, one probably cannot yet expect a consensus conceptualization of communication across disciplines.

Communication Model Terms as provided by Rothwell (11-15):

Noise; interference with effective transmission and reception of a message.

For example;

- physical noise or external noise which are environmental distractions such as poorly heated rooms, startling sounds, appearances of things, music playing some where else, and someone talking really loudly near you.

- physiological noise are biological influences that distract you from communicating competently such as sweaty palms, pounding heart, butterfly in the stomach, induced by speech anxiety, or feeling sick, exhausted at work, the ringing noise in your ear, being really hungry, and if you have a runny noise or a cough.

- psychological noise are the preconception bias and assumptions such as thinking someone who speaks like a valley girl is dumb, or someone from a foreign country can’t speak English well so you speak loudly and slowly to them.

- semantic noise are word choices that are confusing and distracting such as using the word tri-syllabic instead of three syllables.

- Sender; the initiator and encoder of a message

- Receiver; the one that receives the message (the listener) and the decoder of a message

- Decode; translates the senders spoken idea/message into something the receiver understands by using their knowledge of language from personal experience.

- Encode; puts the idea into spoken language while putting their own meaning into the word/message.

- Channel; the medium through which the message travels such as through oral communication (radio, television, phone, in person) or written communication (letters, email, text messages)

- Feedback; the receivers verbal and nonverbal responses to a message such as a nod for understanding (nonverbal), a raised eyebrow for being confused (nonverbal), or asking a question to clarify the message (verbal).

- Message; the verbal and nonverbal components of language that is sent to the receiver by the sender which conveys an idea.

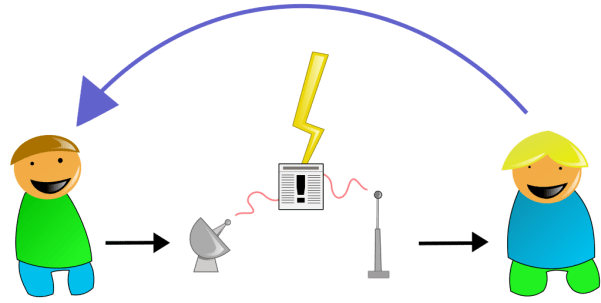

Linear Model – is a one way model to communicate with others. It consists of the sender encoding a message and channeling it to the receiver in the presence of noise. Draw backs – the linear model assumes that there is a clear cut beginning and end to communication. It also displays no feedback from the receiver.

For example; a letter, email, text message, lecture.

The Linear Model

Interactive Model – is two linear models stacked on top of each other. The sender channels a message to the receiver and the receiver then becomes the sender and channels a message to the original sender. This model has added feedback, indicates that communication is not a one way but a two way process. It also has “field of experience” which includes our cultural background, ethnicity geographic location, extend of travel, and general personal experiences accumulated over the course of your lifetime. Draw backs – there is feedback but it is not simultaneous.

The Interactive Model

For example – instant messaging. The sender sends an IM to the receiver, then the original sender has to wait for the IM from the original receiver to react. Or a question/answer session where you just ask a question then you get an answer.

Transactional Model – assumes that people are connected through communication; they engage in transaction. Firstly, it recognizes that each of us is a sender-receiver, not merely a sender or a receiver. Secondly, it recognizes that communication affects all parties involved. So communication is fluid/simultaneous. This is how most conversation are like. The transactional model also contains ellipses that symbolize the communication environment (how you interpret the data that you are given). Where the ellipses meet is the most effect communication area because both communicators share the same meaning of the message.

For example – talking/listening to friends. While your friend is talking you are constantly giving them feedback on what you think through your facial expression verbal feedback without necessarily stopping your friend from talking.

The Transactional Model

History of Communication Theory

The Academic Study of Communication

Communication has existed since the beginning of human beings, but it was not until the 20th century that people began to study the process. As communication technologies developed, so did the serious study of communication. When World War I ended, the interest in studying communication intensified. The social-science study was fully recognized as a legitimate discipline after World War II.

Before becoming simply communication, or communication studies, the discipline was formed from three other major studies: psychology, sociology, and anthropology. Psychology is the study of human behavior, Sociology is the study of society and social process, and anthropology is the study of communication as a factor which develops, maintains, and changes culture. Communication studies focus on communication as central to the human experience, which involves understanding how people behave in creating, exchanging, and interpreting messages.

Communication Theory has one universal law posited by S. F. Scudder (1980). The Universal Communication Law states that, “All living entities, beings and creatures communicate.” All life communicates through movements, sounds, reactions, physical changes, gestures, languages, and breath. Communication is a means of survival. Examples – the cry of a child (communicating that it is hungry, hurt, or cold); the browning of a leaf (communicating that it is dehydrated, thirsty per se, or dying); the cry of an animal (communicating that it is injured, hungry, or angry). Everything living communicates in its quest for survival.”

Communication Theory Framework

It is helpful to examine communication and communication theory through one of the following viewpoints:

- Mechanistic: This view considers communication as a perfect transaction of a message from the sender to the receiver. (as seen in the diagram above)

- Psychological: This view considers communication as the act of sending a message to a receiver, and the feelings and thoughts of the receiver upon interpreting the message.

- Social Constructionist (Symbolic Interactionist): This view considers communication to be the product of the interactants sharing and creating meaning. The Constructionist View can also be defined as, how you say something determines what the message is. The Constructionist View assumes that “truth” and “ideas” are constructed or invented through the social process of communication. Robert T. Craig saw the Constructionist View or the constitutive view as it’s called in his article, as “…an ongoing process that symbolically forms and re-forms our personal identities.” (Craig, 125). The other view of communication, the Transmission Model, sees communication as robotic and computer-like. The Transmission Model sees communication as a way of sending or receiving messages and the perfection of that. But, the Constructionist View sees communications as, “…in human life, info does not behave as simply as bits in an electronic stream. In human life, information flow is far more like an electric current running from one landmine to another” (Lanham, 7). The Constructionist View is a more realistic view of communication because it involves the interacting of human beings and the free sharing of thoughts and ideas. Daniel Chandler looks to prove that the Transmission Model is a lesser way of communicating by saying “The transmission model is not merely a gross over-simplification but a dangerously misleading representation of the nature of human communication” (Chandler, 2). Humans do not communicate simply as computers or robots so that’s why it’s essential to truly understand the Constructionist View of Communication well. We do not simply send facts and data to one another, but we take facts and data and they acquire meaning through the process of communication, or through interaction with others.

- Systemic: This view considers communication to be the new messages created via “through-put”, or what happens as the message is being interpreted and re-interpreted as it travels through people.

- Critical: This view considers communication as a source of power and oppression of individuals and social groups.

Inspection of a particular theory on this level will provide a framework on the nature of communication as seen within the confines of that theory.

Theories can also be studied and organized according to the ontological, epistemological, and axiological framework imposed by the theorist.

Ontology essentially poses the question of what, exactly, it is the theorist is examining. One must consider the very nature of reality. The answer usually falls in one of three realms depending on whether the theorist sees the phenomena through the lens of a realist, nominalist, or social constructionist. Realist perspective views the world objectively, believing that there is a world outside of our own experience and cognitions. Nominalists see the world subjectively, claiming that everything outside of one’s cognitions is simply names and labels. Social constructionists straddle the fence between objective and subjective reality, claiming that reality is what we create together.

Epistemology is an examination of how the theorist studies the chosen phenomena. In studying epistemology, particularly from a positivist perspective, objective knowledge is said to be the result of a systematic look at the causal relationships of phenomena. This knowledge is usually attained through use of the scientific method. Scholars often think that empirical evidence collected in an objective manner is most likely to reflect truth in the findings. Theories of this ilk are usually created to predict a phenomenon. Subjective theory holds that understanding is based on situated knowledge, typically found using interpretative methodology such as ethnography and also interviews. Subjective theories are typically developed to explain or understand phenomena in the social world.

Axiology is concerned with what values drive a theorist to develop a theory. Theorists must be mindful of potential biases so that they will not influence or skew their findings (Miller, 21-23).

Mapping the theoretical landscape

A discipline gets defined in large part by its theoretical structure. Communication studies often borrow theories from other social sciences. This theoretical variation makes it difficult to come to terms with the field as a whole. That said, some common taxonomies exist that serve to divide up the range of communication research. Two common mappings involve contexts and assumptions.

Contexts

Many authors and researchers divide communication by what they sometimes called “contexts” or “levels”, but which more often represent institutional histories. The study of communication in the US, while occurring within departments of psychology, sociology, linguistics, and anthropology (among others), generally developed from schools of rhetoric and from schools of journalism. While many of these have become “departments of communication”, they often retain their historical roots, adhering largely to theories from speech communication in the former case, and from mass media in the latter. The great divide between speech communication and mass communication becomes complicated by a number of smaller sub-areas of communication research, including intercultural and international communication, small group communication, communication technology, policy and legal studies of communication, telecommunication, and work done under a variety of other labels. Some of these departments take a largely social-scientific perspective, others tend more heavily toward the humanities, and still others gear themselves more toward production and professional preparation.

These “levels” of communication provide some way of grouping communication theories, but inevitably, some theories and concepts leak from one area to another, or fail to find a home at all.

The Constitutive Metamodel

Another way of dividing up the communication field emphasizes the assumptions that undergird particular theories, models, and approaches. Robert T. Craig suggests that the field of communication as a whole can be understood as several different traditions who have a specific view on communication. By showing the similarities and differences between these traditions, Craig argues that the different traditions will be able to engage each other in dialogue rather than ignore each other. Craig proposes seven different traditions which are:

- Rhetorical: views communication as the practical art of discourse.

- Semiotic: views communication as the mediation by signs.

- Phenomenological: communication is the experience of dialogue with others.

- Cybernetic: communication is the flow of information.

- Socio-psychological: communication is the interaction of individuals.

- Socio-cultural: communication is the production and reproduction of the social order.

- Critical: communication is the process in which all assumptions can be challenged.

Craig finds each of these clearly defined against the others, and remaining cohesive approaches to describing communicative behavior. As a taxonomic aid, these labels help to organize theory by its assumptions, and help researchers to understand why some theories may seem incommensurable.

While communication theorists very commonly use these two approaches, theorists decentralize the place of language and machines as communicative technologies. The idea (as argued by Vygotsky) of communication as the primary tool of a species defined by its tools remains on the outskirts of communication theory. It finds some representation in the Toronto School of communication theory (alternatively sometimes called medium theory) as represented by the work of Innis, McLuhan, and others. It seems that the ways in which individuals and groups use the technologies of communication — and in some cases are used by them — remain central to what communication researchers do. The ideas that surround this, and in particular the place of persuasion, remain constants across both the “traditions” and “levels” of communication theory.

Toronto School of communication theory

“Faced with information overload, we have no alternative but pattern recognition.”—Marshall McLuhan

The Toronto School is a school of thought in communication theory and literary criticism, the principles of which were developed chiefly by scholars at the University of Toronto. It is characterized by exploration of Ancient Greek literature and the theoretical view that communication systems create psychological and social states. The school originated from the works of Eric A. Havelock and Harold Innis in the 1930s, and grew to prominence with the contributions of Edmund Snow Carpenter, Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan.

Since 1963, the McLuhan Program in Culture and Technology at the University of Toronto Faculty of Information has carried the mandate for teaching and advancing the school. Notable contemporary scholars associated with the Toronto School include Derrick de Kerckhove, Robert K. Logan and Barry Wellman.

History and development

The Toronto School has been described as “the theory of the primacy of communication in the structuring of human cultures and the structuring of the human mind.” Eric Havelock’s studies in the transitions from orality to literacy, as an account of communication, profoundly affected the media theories of Harold Innis and Marshall McLuhan. Harold Innis’ theories of political economy, media and society had a significant influence on critical media theory and communications and with McLuhan, offered groundbreaking Canadian perspectives on the function of communication technologies as key agents in social and historical change. Together, their works advanced a theory of history in which communication is central to social change and transformation.

In the early 1950s, McLuhan began the Communication and Culture seminars, funded by the Ford Foundation, at the University of Toronto. As his reputation grew, he received a growing number of offers from other universities and, to keep him, the university created the Centre for Culture and Technology in 1963. He published his first major work during this period: The Mechanical Bride (1951) was an examination of the effect of advertising on society and culture. He also produced an important journal, Explorations, with Edmund Carpenter, throughout the 1950s. With Innis, Havelock, Derrick de Kerckhove and Barry Wellman, McLuhan and Carpenter have been characterized as the Toronto School of Communication. McLuhan remained at the University of Toronto through 1979, spending much of this time as head of his Centre for Culture and Technology.

Key works

Empire and Communications

Published in 1950 by Harold Innis’s Empire and Communications is based on six lectures he delivered at Oxford University in 1948. The series, known as the Beit Lectures, was dedicated to exploring British imperial history. Innis however, decided to undertake a sweeping historical survey of how communications media influence the rise and fall of empires. He traced the effects of media such as stone, clay, papyrus, parchment and paper from ancient to modern times.

Innis argued that the “bias” of each medium either toward space or toward time helps determine the nature of the civilization in which that medium dominates. “Media that emphasize time are those that are durable in character such as parchment, clay and stone,” he writes in his introduction. These media tend to favour decentralization. “Media that emphasize space are apt to be less durable and light in character, such as papyrus and paper.” These media generally favour large, centralized administrations. Innis believed that to persist in time and to occupy space, empires needed to strike a balance between time-biased and space-biased media. Such a balance is likely to be threatened however, when monopolies of knowledge exist favouring some media over others.

The Bias of Communication

In his 1947 presidential address to the Royal Society of Canada, Innis remarked: “I have attempted to suggest that Western civilization has been profoundly influenced by communication and that marked changes in communications have had important implications.” He went on to mention the evolution of communications media from the cuneiform script inscribed on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia to the advent of radio in the 20th century. “In each period I have attempted to trace the implications of the media of communication for the character of knowledge and to suggest that a monopoly or oligopoly of knowledge is built up to the point that equilibrium is disturbed.” Innis argued, for example, that a “complex system of writing” such as cuneiform script resulted in the growth of a “special class” of scribes. The long training required to master such writing ensured that relatively few people would belong to this privileged and aristocratic class. As Paul Heyer explains:

In the beginning, which for Innis means Mesopotamia, there was clay, the reed stylus used to write on it, and the wedge-shaped cuneiform script. Thus did civilization arise, along with an elite group of scribe priests who eventually codified laws. Egypt followed suit, using papyrus, the brush, and hieroglyphic writing.

The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962)

Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (1951) is a study in the field now known as popular culture. His interest in the critical study of popular culture was influenced by the 1933 book Culture and Environment by F.R. Leavis and Denys Thompson, and the title The Mechanical Bride is derived from a piece by the Dadaist artist, Marcel Duchamp.

The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (written in 1961, first published in Canada by University of Toronto Press in 1962) is a study in the fields of oral culture, print culture, cultural studies, and media ecology. Throughout the book, McLuhan takes pains to reveal how communication technology (alphabetic writing, the printing press, and the electronic media) affects cognitive organization, which in turn has profound ramifications for social organization:

…[I]f a new technology extends one or more of our senses outside us into the social world, then new ratios among all of our senses will occur in that particular culture. It is comparable to what happens when a new note is added to a melody. And when the sense ratios alter in any culture then what had appeared lucid before may suddenly become opaque, and what had been vague or opaque will become translucent.

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964)

McLuhan’s most widely known work, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), is a study in media theory. In it McLuhan proposed that media themselves, not the content they carry, should be the focus of study — popularly quoted as “the medium is the message”. McLuhan’s insight was that a medium affects the society in which it plays a role not by the content delivered over the medium, but by the characteristics of the medium itself. McLuhan pointed to the light bulb as a clear demonstration of this concept. A light bulb does not have content in the way that a newspaper has articles or a television has programs, yet it is a medium that has a social effect; that is, a light bulb enables people to create spaces during nighttime that would otherwise be enveloped by darkness. He describes the light bulb as a medium without any content. McLuhan states that “a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence.” More controversially, he postulated that content had little effect on society — in other words, it did not matter if television broadcasts children’s shows or violent programming, to illustrate one example — the effect of television on society would be identical. He noted that all media have characteristics that engage the viewer in different ways; for instance, a passage in a book could be reread at will, but a movie had to be screened again in its entirety to study any individual part of it.